The second day of the 9th edition of The Power of Storytelling brought us a carousel of emotions, and inspiring speeches about healing, family histories and passion for storytelling.

Take a look at a summary of what our last nine speakers shared on Saturday.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL

Jonathan, author of The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, believes that what sets humans apart from other species is the “un-rush of data in our brain, struggling to impose meaningful comforting story structures to the chaos around us”.

He also shared with the audience the ways in which storytelling can go wrong: “there is a tendency for human beings to glue onto a narrative for no good reason at all, tenaciously, using it to project patterns around the world that are not there”. Sometimes, he says, we allow our narratives to choose our facts.

But good stories “give us a state of consciousness, a hyper state of attention”.

“We think of storytellers as metaphorical bruisers: they hook us, revive us, transfix us. Transfixing – that is what you do to a butterfly, stabbing it to a cork board, being held in place. Storytellers are manipulating. Like lovers, they infatuate us, infect us, seduce us. They are like natural forces, like floods, rivers, like winds – they sweep us up, carry us away. They are like wizards who enchant us, bewitch us, hypnotise.”

“Storytellers shape minds, shape cultures and will help to author the future,” Jonathan explained. “The question is: will they ride us to a brighter world or a darker one?”

EVAN RATLIFF

Evan explained his fascination with villains and what this type of stories can show readers about human beings and their motivations.

„I really kind of love bad people. I love scammers, hackers, thieves, people who fake their death and leave their families behind, drug dealers. I am fascinated with them, I spend time thinking about them, I leave my family and fly across the world to meet these mostly terrible men. I hear their stories without judgement and go home to spend more time thinking about them,” Evan confessed at the beginning of his speech.

Asking himself why that is and what can we learn from the worst people among us, he took us through the stories of some of the dangerous men he’d interviewed and his new book, The Mastermind: Drugs. Empire. Murder. Betrayal. In the book, he focused on the case of Paul Le Roux and his cronies, who built one of the biggest high tech crime organization in the world – he even had an “office” in Romania.

“By the end of my reporting, I discovered Paul had a hit list – journalists, judges, people who owed him as little as 1.000 dollars. I started thinking of him as an alternate world version of a modern tech founder: sort of potentially brilliant in tech, gifted, nerdy people who have the ability to change the world. But those guys went down one path, he went down another path to build a unicorn organization outside of the law. An organization worth more than Facebook in 2008,” Evan explained. The Mastermind took him all over the world interviewing people who had worked for Paul and his victims.

“Where is the healing in telling a story like that? Aren’t these people just evil or psychotic? I think about these questions and try to use them to animate my writing. My first thought is not every story has to change the world for the better,” Evan explained. “Their impact is very difficult to predict and stories can be entertaining, crazy, mind-blowing – there are lots of reasons for stories to exist.

But that might not be enough in cases when people really got hurt. I think we need to do more when it comes to stories that are particularly dark. I respect people who say they don’t have time or appreciation for this type of story. At their best, these stories are not just about the Pauls of the world, but they can illuminate the systems that allowed them to flourish. It’s about the opioid crisis in the US, and a 15-year-old kid who can order those online and have them delivered to their door, about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and what happened to soldiers there. Where do you think some of them will end up? It’s a story about corruption, where Paul bought judges. About a president who murdered tens of thousands of people for a “war on drugs”. About justice, who gets pursued and who doesn’t. And what it means to prosecute the war on drugs with unlimited leverage.”

There’s also a second reason why Evan is fascinated with people who do bad things.

“They can be conveyance mechanisms for morality. It’s not like we’re all one step away from becoming assassins, but they can give us a window into understanding human motivations. People like Marcus, who I found after working for years, they were weirdly thankful I was telling their stories because they needed it, they were sometimes confused about the choices they made and ashamed. When you look at any sort of evil act from a distance you can describe it like that, just evil, and you might be right. But if you look closer, you can see the steps and little compromises people made that landed them into that place to do something terrible.”

“By the end, I thought of Paul as existing on the same curve as the people from Facebook, even if his was a much more extreme approach. We’re seeing those impulses all around us. The difference between Paul and what happened with Facebook surrounding the elections, surrounding genocide in parts of the world, is a difference in severity, not in kind. It’s about how people are approaching what they’re putting out in the world. Our lives are affected by people like this. Sometimes our countries are led by people like this, who’ve followed the siren song of compromising their morality.”

AARON WICKENDEN

Award-winning documentary film-maker Aaron Wickenden shared with the audience the core ideas of his craft and his intimate approach of reality, including how he deals with the modulations of life and emotions.

“To me, emotional communication is the only communication that has the potential to heal,” Aaron said.

In Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, a film about TV host, puppeteer and educator Fred Rogers, that became one of Barrack Obama’s favorite documentaries, Aaron wanted to portray someone who spent his life helping kids navigate the difficult modulations of life – divorce, nuclear war or race.

“For me and many others, Mr. Rogers is a master modulator, operating in that place where people feel most wounded and scared. He considered his relationship with the audience as a sacred space.”

“Diving into emotions and working through stories has been an unlikely thing for me to do,” Aaron confessed. “I come from a family of sailors, not storytellers (…) But my generation became hyper-sensitive to emotion, we wanted to explore the difficult topics. I wanted to figure out how to connect to others in an emotionally honest and deep way.”

Above his computer monitor, Aaron has a post-it with one question: “to what end?”. It reminds him to think how any movie he’s making is useful and how it makes people better equipped for life’s modulations.

LISA TADDEO

Pushcart Prize winner and bestselling author Lisa Taddeo talked about the process behind her amazing non-fiction debut, Three Women, which studies the desires of three women over eight years and offers us intimate access into their emotional and erotic lives. While documenting the book, she went as far as travel the US six times looking for stories, and moving into the towns of the women she was writing about.

“It felt good and moral to do that, to talk to people at length and candour. You have to not make it about journalism, but humanity,” Lisa said.

“It’s important to tell all stories, especially the unheard ones. People ask me why there are no men in the book. Because it was the women’s stories, it was their version of the events. The men’s stories have been heard.

There is more than one way to tell a story, there are a thousand ways and we should try and tell them all. In telling stories of real people with real nuance, we help show there is no evil or good, no black or white, just grey, awesome, passionate life. As writers and storytellers, we need to listen more than we ask and we need to write the truth, not only the facts.”

What she felt like she accomplished with her book was to have someone’s story be heard. “It meant a lot,” she said, because truth can be scary and people aren’t ready yet to deal with all the nuances of life.

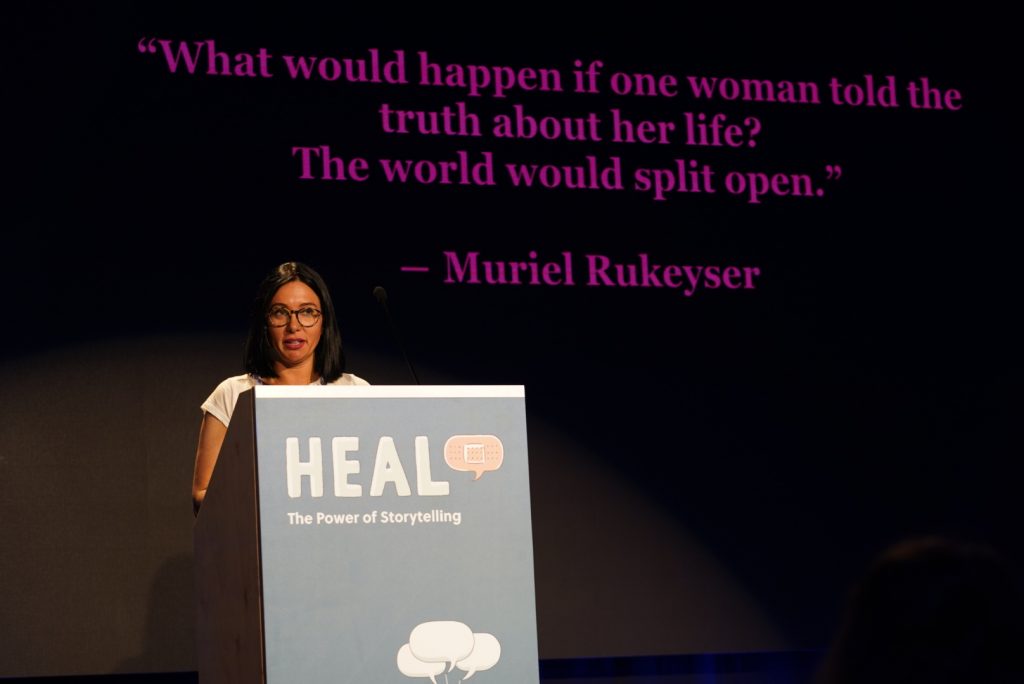

ANN MARIE LIPINSKI

Pulitzer Prize-winning Ann Marie Lipinski, the curator of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University, gave an emotional talk about journalism in our day and age, and how journalists should be able to answer the question of “Why do I do what I do?” repeatedly over the years, in order to frame and re-frame the past, the present and the future of this important work.

She explained the concept of “sounding”, when people gather in groups and tell their stories, creating a bridge from the past to the person they’ve become or will become. “Make time for this,” Ann Marie said, because “not making time comes with a cost”.

She has been asking the above-mentioned question of journalists for eight years now, pushing them to move past the easy answers. For her, the answer came from the upbringing her grandmother gave her and the stories they shared.

“My grandmother was training me to report, to find the real stories no soap opera can replicate. She did not embellish, she told things in the precise order they happened, she had a nag of holding the extraordinary in every day. She knew what made the extraordinary. Life at its simplest, even now, is my favorite form of journalism. All these years later, I am still hungrily reporting my grandmother’s stories.”

Each of us can benefit from the deep reflection necessary to honestly answer that question. It’s something we can hold tight to in dark times or challenges of the professions we’ve chose. “Stories, like prayers, are petitions for change,” Ann Marie said.

At the end of her speech, Ann Marie shared the story of another journalist she knew who had doubts about the profession: „Sometimes my doubts of journalism are as powerful as the ones felt in church. I thought of leaving more than once. But I stay not because I believe in the institution or impact, I believe in the practice of prayer, in raising my mind and heart in requesting good things from an audience, even if no good is coming. Every story is a prayer, even on my worst day. My profession is to tell those stories”.

KATE SAMWORTH

Kate sees herself as a narrative painter, who tells stories through pictures. “I always wanted to be a writer, but painting is easier for me,” she told the audience at #Story19.

When she was little, Kate loved reading and creating dioramas, and when she realized she could create a whole world using one-point perspective, she believed that was all she wanted to do. She was fascinated even with older paintings, how you could stare at one and have secret conversations with someone from the past.

Kate believes her art was most influenced not by other painters, but by her favorite writers: Mark Twain and Kurt Vonnegut. “We share the same perspectives on the world, on war and I think I want my art to do what they did in writing.”

She began painting allegories and then moved on to satirical work, while also playing in an all-girl punk band and getting more and more involved in political protests in the US. As for her painting, Kate realised she didn’t want to create abstract art, but art that is rooted into reality. She found a fantastic teacher who could help her with that, so she moved to New Orleans to attend his new art school. From there, she went to Brazil and became a tour guide for a few months in the dreamy region of Bahia.

Upon returning to the States, she realized environmental issues mattered to her a lot, she was reading articles and books and studies about that, and she felt a sense of urgency to do something. That’s how she decided to paint about the natural world and its misuse by humans. She does it in a funny, magical and non-didactic way, like in the illustrated book Aviary Wonders Inc. from 2014, set in the near future and based on the premise that the bird populations on Earth are in perilous decline.

After the last presidential elections in the US, she felt people became very divided and she felt hurt by the tense conversations around her, so she created an Antidote Series, imagining humans and animals living in communion and inviting each other in their spaces, interacting over dinner or music through non-verbal communication.

“I steered my boat four degrees towards optimism,” Kate funnily told everyone at the conference.

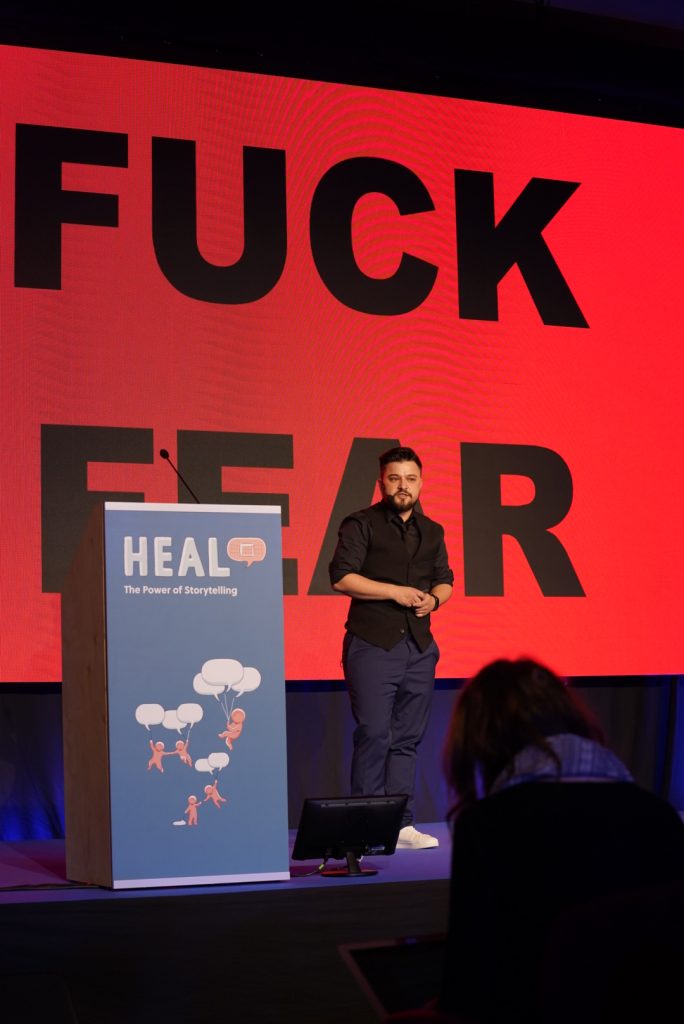

PATRICK BRĂILA

Patrick Brăila described himself as “a transgender activist, film director, sometimes performer, tired, and angry”.

“I haven’t always been tired and angry,” he said. “I was a very loved child. I grew up in a village in South-Western Romania, in my grandparents’ house, both of whom were teachers. I understand that being brought up with love is at the basis of my emotional intelligence. But I was raised as a girl.”

Growing older, Patrick found it harder and harder to deny his true identity and he felt a disconnect between himself and his female body. He went through depression and saw himself as “a rat, unworthy of being among people”. But he owed it to himself to at least try and become who he really was. It took him 12 years to transition, buying illegal testosterone online because it’s so hard to find in Romania – it’s a struggle the whole trans community goes through in our country.

He understood the best way to change mentalities was to share his story and, for a while, that brought him closer to other people and gave him satisfaction. But about four years into activism, more and more members of the community started dying. He told the story of Laura, a trans woman and sex worker stabbed to death by a client when he realised she was trans, and of a trans woman in Focșani whom Patrick met once and then found out she had been found dead on the streets of Munich. The police didn’t investigate and her family couldn’t afford to even bring the body back to Romania, so she’s buried somewhere in Germany.

“So I am angry and I express it. It’s been so long since I felt anger and I said all the time that I’m fine, I’m fine,” Patrick said, explaining how he chooses to navigate this difficult time.

“Trying to stay kind: this is my bet. To continue to be kind and fair, and pay attention to everyone around me and not do any harm. This is my bet, and while doing all of this, I wish to continue to find myself, because living in a cage for 12 years leaves you a bit behind and I feel sometimes in a race to catch up on life, while making my community resilient and strong.

But there are moments when I am left alone at home and my anger becomes pain. It’s a good thing I am an artist and a film maker, so I will make a movie about myself. After finishing my first film, an autobiographical short, I told myself I would never do it again. But I am starting a feature length documentary about myself, about facing the authorities, trying to change my ID, having to go to court, bringing evidence, witnesses, letting a judge decide if you are who you say you are. In my home, alone, there is pain but I film it and show it and it’s my way of healing.” Patrick is proud to see a new generation of trans people in Romania assuming their identities, being willing to talk about it publicly and it makes him think all of his efforts weren’t in vain. So he has a message to the shame and fear that plagues his earlier life: “Fuck shame. Fuck fear. Be your true self”.

LULU MILLER

Can stories heal?

The question gnawed at Lulu Miller’s psyche ever since she heard about the theme of the conference. The Invisibilia podcast co-host explored that question at #Story19 through a powerful story about her big sister, Abby, her family and mental health.

“Abby, my sister, was a really jolly baby. As she grew up, she was still jolly, but a lot of anxiety came in, and learning and social disabilities which made school really hard for her. She had to drop out of school because of bullying. She got worse, had huge breakdowns. I’m not bringing up her diagnosis because even doctors couldn’t decide on it. Eventually my parents had her institutionalized, but then brought her home shortly after because she was overmedicated,” Lulu shared.

For a long time, she believed that all of her sister’s problems came from the outside world and that if everyone had a family member with a mental disability, they would stop freaking out over it. “It was the story I told myself again and again: she could be healed if everyone understood.”

Year later, Lulu ended up documenting the Belgian town of Geel, where for 700 years residents had taken in people with mental health issues – 25% of the town was mentally ill. What she realized, being there, was that it was hard to tell the difference between the “sane and insane” because everyone was treated with the same respect and dignity.

“I remember thinking: oh my God! This is the land that could heal my sister. An upside down town where the abnormal was normal,” Lulu said.

Talking to the head psychologist in the programme, she learned that sometimes people who are not your biological family can provide better care for you in times of mental stress. “It’s the Law of expressed emotion. Often, our words have nothing to do with our emotions and we’re expressing them non-verbally. He said in a family unit we express emotion at higher levels. And there are three emotions that are particularly toxic to mental illness patients: hostility, criticism, and emotional over engagement (constantly worrying and checking on them). It’s two times more likely to trigger relapse. That got me thinking about my family and Abby. Even my desire of an alternate culture that could fix her, a different land. Even my parents always tried to fix her – conveying a message that who she was wasn’t OK.”

She shared these ideas with her parents and proposed that acceptance is what can actually heal a person rather than obsessing over their care and medication. The relationship with her sister improved, and so did her mental state – but not completely.

“So I believe stories have that power to make things better, the potential to heal, but not to make things perfect. Almost every story I’ve ever done has been about how a small story can have a huge impact on someone’s life. (…) But I am increasingly interested in investigating the place behind the stories: reality. However bleak it might be. I’m curious to see how it turns out.”

JACQUI BANASZYNSKI

The Fairy Godmother of our conference, Pulitzer Prize-winning Jacqui Banaszynski, closed our two-day event with a heart-warming speech about healing our lifelong baggage.

“A call for healing couldn’t be more timely,” Jacqui began. “I’m older than most of you, I have lived through the soundtrack of civil wars. I was not 16 when Martin Luther King was assassinated, I had just turned 16 when Bobby Kennedy was gunned down following a presidential campaign speech. I was a senior in high school when four college students were shot to death by our national guard as they protested. I was a journalism student when Watergate broke,” Jacqui enumerated. She saw the struggle of the women’s movement, the HIV epidemic, LGBT+ people fighting for equal rights, the shaming of women who wanted abortion legalized or rape thoroughly investigated. After all this, there was 9/11.

She said the times we’re living now feel especially dark, with white nationalism spreading blood lust, portraying people at “The Other”. But when she’s on the edge of despair, she tries to ask herself if “today is as broken as it feels”.

“What if you could go back and ask people about Soviet life, or go into a Roma village? What if we could ask and what if we could listen? Would their stories help us heal?”

Even though her faith in stories has sometimes dwindled, she believes “because of stories we have a glimpse in the past so we can put things into perspective”. Stories taught her the most about the kind of journalist and person she wanted to be. And they did manage to heal people, even if only metaphorically.

“Our story didn’t heal a terminal illness,” she said of her Pulitzer-winning series about a gay couple dying of AIDS in the rural America of the 1980s. “But it eased a terminal despair.”

Her own baggage, stemming mostly from the fraught relationship with her father, was also relieved with the help of stories, of understanding the dynamic between her parents and learning about how they fell in love.

”We all have baggage. We pack them with us, drag it along even when we think we leave it in our notebook, pushing us forward or holding us back, but demanding to be reclaimed. Like when you’re on an airplane. Think about it: your baggage has to be with you all the time, so you better know how to pack.”

“When my turn comes, I will cherish every story I have had the honor of hearing and only feel sorry I haven’t have the time to hear more.”

Thank you all for being with us for the 9th edition and mark your calendars for next year: October 16-18.

Make sure to check out the takeaways from Day 1 as well.

Photos by Cătălin Georgescu and Vlad Cupșa.